Host a Voting Party!

We got great coverage of our voting party in Sunday’s Oregonian. And when it rains, of course it pours – a LTE of mine made it into the paper today vis voting no on Measure 64.

Text of the voting party article:

Oregon leads the way in loving vote-by-mail

by Michelle Cole, The Oregonian

The host wore an Obama T-shirt and played “So Happy Together” on his guitar. His guests sang along, drank wine and ate homemade pie bursting with elderberries and apples picked in the Columbia River Gorge.

Forget about stuffy polling booths, hanging chads and long lines — this is how Oregon votes. We throw parties where people mark their ballots. Or we sit with family at the kitchen table and discuss our choices.

“We have a social responsibility to vote, and it should be a community effort, not just a solo effort,” said Jef Murphy, who joined two dozen others at a voting party in Portland on Wednesday night.Ten years ago, Oregon became the first and only state to agree to vote by mail exclusively. Just as with our bottle and beach bills, Oregon is proud of being first.

The trend is catching on. This year, an estimated 30 percent of the nation’s voters will cast ballots either by mail or by visiting the polls ahead of Election Day.

So what might Oregon’s experiment with vote by mail teach the nation?

First, it’s a different way of voting, but it hasn’t proved to be as “un-American” as some people claimed.

In the 1980s, when the Oregon Legislature first approved voting by mail on a limited basis, critics warned that the integrity of the process would be undermined.

“There was always this accusation of fraud, of voting under duress, people taking your ballot and somehow tampering with it,” said Senate President Peter Courtney, a Salem Democrat who sponsored a vote-by-mail bill in 1981, his first year in the Legislature.

Voting Q & A

Voters across the country are rightly concerned about the security of their ballots. To answer those questions about Oregon, The Oregonian talked to Secretary of State Bill Bradbury, State Elections Director John Lindback, and Multnomah County Elections Director Tim Scott.

Q: What’s all this about some group called Acorn registering fake names and fake addresses, including the starting lineup of the Dallas Cowboys football team? Is that happening in Oregon?

A: Acorn, or the Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now, is a national nonpartisan group that registers voters. The group is being investigated in Nevada and several other states for turning in duplicate or fraudulent cards. There have been a handful of complaints regarding out-of-state registration groups in Oregon, but none related to Acorn. Oregon prohibits paying registration canvassers for each registration they collect, which has been a problem with Acorn.

Q: So let’s say I register to vote for the first time. How do you know it’s actually me?

A: Your registration card goes to the local county elections office, which inputs the information into a centralized database. If you’ve listed a driver’s license or identification number, the system automatically checks the DMV database for a match. If you don’t have a driver’s license and have provided the last four digits of your Social Security number, the system checks against the federal SSA database. If there’s no match, the county elections office will contact you to get further documentation.

Q: What happens if I never send the requested documentation?

A: You still get a ballot and you can cast that ballot, but none of your votes for federal races will count. Your votes in local and state contests still count.

Q: How many people are out there who haven’t provided documentation?

A: Very few, say elections officials. For example, there are 3,100 cases pending in Multnomah County where people have not met federal identification requirements. That’s 0.7 percent of 435,000 registered voters.

Q: How often do counties purge voter registration rolls?

A: National law requires voters to be notified before they’re purged. In Oregon, voters move to the “inactive” list if they haven’t voted in five years. At that point, the county sends a card asking to verify their registration. Voters stay on the inactive list through two more federal election cycles, though they won’t get ballots, and then they’re canceled.

Q: What happens to ballots after they’re mailed in?

A: Each county has its own system, but the basics are the same. In Multnomah County, elections staff check signatures and sort ballots by precinct as soon as they arrive. One week before Election Day, citizen boards open the ballots and check for erasures and stray marks that might mess up the scanner. The ballots aren’t counted until Election Day.

Q: How do I know I’m registered?

A: Go online and plug in your name and birth date: www.sos.state.or.us/elections

Q: I’ve moved. What should I do?

A: Call or stop by your county elections office to update your information. You can do that until 8 p.m. on Nov. 4, which is when voting ends.

— Janie Har

Courtney said he and his colleagues had no “grand design” in mind. They simply wanted to improve voter turnout. But they were lambasted by critics, he remembers.

“People said: ‘If you respected the right to vote, you ought to be willing to go to the voting booth. It’s your duty.'”

Oregon officials cautiously waded into vote by mail by allowing it only in some local elections. People still had to go to the polls to vote in primary and general elections until 1998, when voters overwhelming approved Measure 60, which made every Oregon election vote by mail.

Phil Keisling, the former secretary of state who championed Measure 60, said there have been “scattered examples” of voter fraud involving mail balloting.”No system is failsafe,” he said. “I prosecuted a county commissioner in Curry County who forged his wife’s signature on a ballot involving his own recall election. He handily won the recall attempt, but he lost his office because he was convicted of a felony.”

The voter’s signature on the back of the return envelope is a key component in ensuring the system’s integrity.

Voters’ signatures are scanned into a computer database and then examined by elections workers who have been trained by an Oregon State Police handwriting expert. Those that don’t match get a letter with a new registration card asking them to complete and return the new card. If a new card is returned and the signature is matched, the ballot can be counted.

All that is fine, said Curtis Gans, director of the Center for the Study of the American Electorate at American University and a critic of vote by mail. Oregon doesn’t have a history of fraud, he concedes. But Gans still worries about the trend toward mail balloting in other states.

“There are places where we know votes have been bought,” he said. “We established the secret ballot to eliminate the pressure of party bosses.”

James Hicks, research director of the Early Voting Information Center at Reed College, said Oregon remains the only state to use mail balloting exclusively, though Washington is close to it.

Twenty-eight states allow what’s called “no excuse” absentee mail balloting. Thirty-one states allow voters to cast ballots ahead of Election Day.

Based on early voting so far, Hicks said, this year may see a record number of people voting ahead of Nov. 4.

Oregon officials learned early on that voters liked casting ballots by mail.

Even before Measure 60 passed, Vicki Paulk, director of Multnomah County Elections from 1984 to 2002, encouraged voters to take advantage of loosening restrictions on absentee voting.

Was Paulk, who used the name Vicki Ervin back then, forging ahead of the change?

Not quite, she said, laughing. “I’m all for public education. … Let’s just say I made it easy for them to take advantage of (mail voting).”

Counties have seen their postage costs increase with all-mail balloting. At the same time, elections officials say, the overall cost of running a mail election is far lower than a poll election.

At one time, Multnomah County had 2,000 people working at hundreds of polling places. This election, there will be 200 to 300 people working at a single office, said elections director Tim Scott.

A few promises made about vote by mail haven’t proved exactly true.For example, political scientists say vote by mail hasn’t translated into a huge increase in voter turnout in national elections, though local and off-year elections have seen a boost.

A study by Gans’ Center for the Study of the American Electorate showed Oregon had the fifth-highest turnout of eligible voters in the 2004 presidential election. But nine states and the District of Columbia recorded greater increases in turnout than Oregon.

Proponents of all-mail voting once suggested that Oregon would see fewer negative ads or last-minute attack ads. And critics, including Gans, said early balloting takes away a voters’ choice if circumstances change.

Statistics indicate, however, that Oregon voters are waiting longer to return their ballots. And it doesn’t take a political scientist to debunk the myth about fewer negative ads.

“The dynamics that have encouraged negative advertising have been even fiercer in the last decade than even I suspected,” Keisling said.

Still, in the decade since Measure 60, he said, one of his biggest surprises is just how much Oregonians love voting by mail.

That sentiment was echoed at Wednesday night’s voting party in Portland.

“I’m glad we’re here as a group, trying to figure out these things together,” Tuolovme Levenstein said.

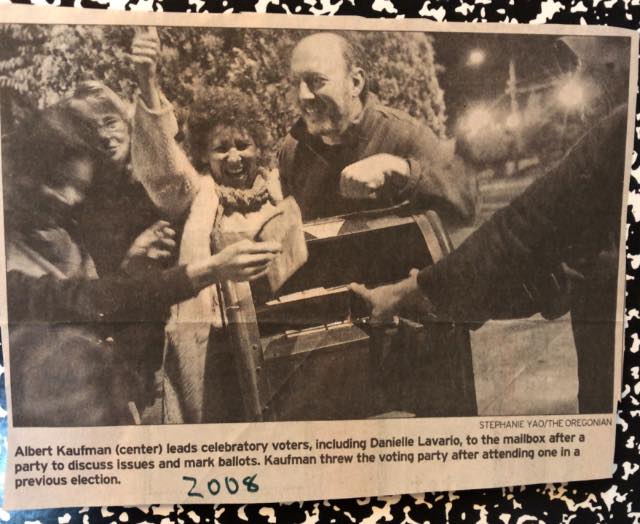

Led by their host, Albert Kaufman, partygoers spent more than two hours working their way down their ballots. They spent only 30 seconds talking about the presidential candidates and a minute or two on the U.S. Senate race. But the group carefully considered candidates for the Soil and Water Conservation District and spent several minutes debating the state treasurer, teacher merit pay, open primaries and a proposed zoo bond.

About 9:30 p.m., Kaufman offered stamps to those who wanted them, and then he and several others walked to the mailbox.

Levenstein decided to hold her ballot a little while longer. She enjoyed the debate, the give and take, she said. But she hadn’t made up her mind on a couple of things.

After all, vote by mail not only allows voters to gather. It also gives a voter time to think.

— Michelle Cole